An ‘XCOM for cats’ from the makers of the Binding of Isaac, Mewgenics is an infernal machine that runs on everyone’s favourite reprobates

Litter big planet.

One of the greatest things on earth is when you’re talking to someone you sort of know and they quietly switch from talking about human friends or family members to talking about their cats. It’s great because there’s often no meaningful alteration in tone to tell you something has changed. Cats are frequently introduced into conversation the same way a person might start talking about an intermittently beloved uncle who’s just out of prison. Cats are often delightful reprobates and oddballs. They’re needlessly, inventively cruel, or inhumanly calm and forbearing, or they’re ostentatiously silly. One will sit on the landing and swipe at everyone. Another will hide under a bath mat, certain that they have attained complete invisibility. They are known by their names but also by their behaviours.

The cats in Mewgenics are known by their behaviours.

Mewgenics – strange harmony here: Francis Galton, cousin of Darwin and originator of the racist pseudoscience of eugenics, also published a paper called Three Generations of Lunatic Cats – is all about cats and what they get up to. An easy way in might be to see it as a kind of XCOM for cats. You gather a gang of four cats and then take them out on a violent adventure, moving through different cat-adjacent spaces – caves, sewers – and engaging in turn-based battles with the various creeping horrors you find there.

In battles, the cats rove about a grid and use a variety of attacks or passive abilities to defeat everyone they’re up against before moving on. Each adventure is a kind of roguelite run, so alongside battles and bosses you’ll encounter little vignettes that could turn out to be good or bad – eat the mystery meat? – or treasure chests, or branching paths that allow you to take a different route depending on how good you’re feeling about your chances.

So why is it called Mewgenics and not, say, XCOM: Enemy’s Gone and Dumped on the Carpet? This is because after a run, you retire your cats and they go and live in a house together. Well, sometimes they do. Because where XCOM had a bit of base-building, Mewgenics has a whole machine that runs on cats. Strays come by and can be dropped into the house to then take out on new adventures. Retired cats can mate and create kittens that can grow up and – you’re with me – be taken out on new adventures with the former strays. Fine.

But then it gets weird. Because around your house is a whole town of people who will give you things in return for cats. This upgrade system is decidedly non-fun, and all the more brilliantly squeamish for it. Someone in town wants retired cats in return for adding a new room to your house. Someone wants kittens to teach you about cat ancestry. Someone wants dead cats. Of course they do. The machine that runs on cats chugs along and you exchange your cats judiciously to expand your house, to get a bigger stash, to learn more about the world of Mewgenics and cat breeding all that jazz.

Caption

Attribution

Oh yes, cat breeding. I’m still early on in this dazzlingly rich and complex game but I’m already understanding that success in the long term revolves around breeding cats and making sure you like the outcomes. Cats have traits and abilities that are useful in battle, but because you can only take a cat out for one roguelite run before it’s retired, you need to be careful about then breeding your retired cats to keep the traits and abilities you like in play. The right environment helps: certain rooms boost your chances of interesting mutations or of healing damage or of passing on better abilities. Further on in the breeding distance – this is a thing? – lies new class abilities, which opens the door to multiclassing. Hold me.

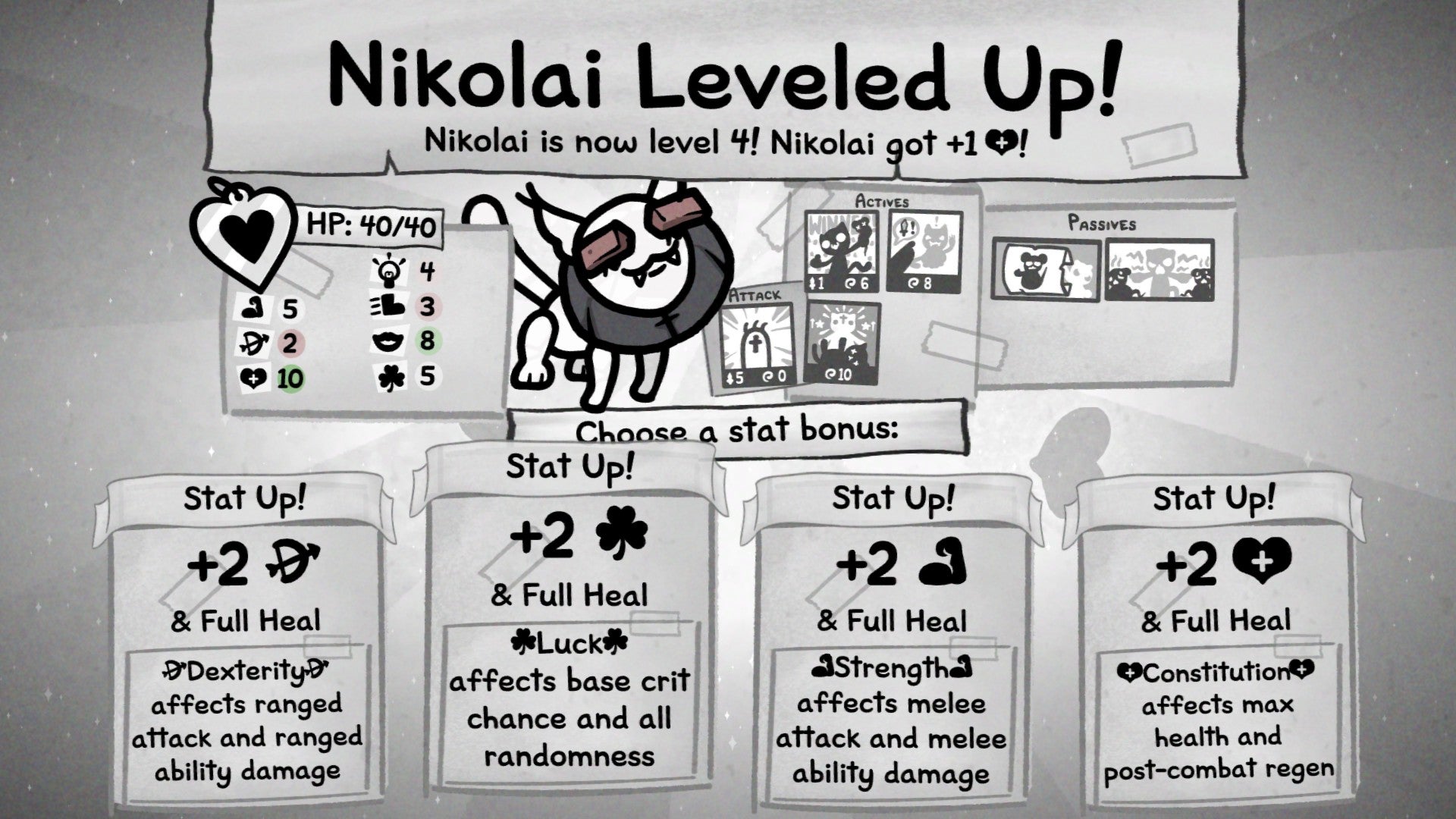

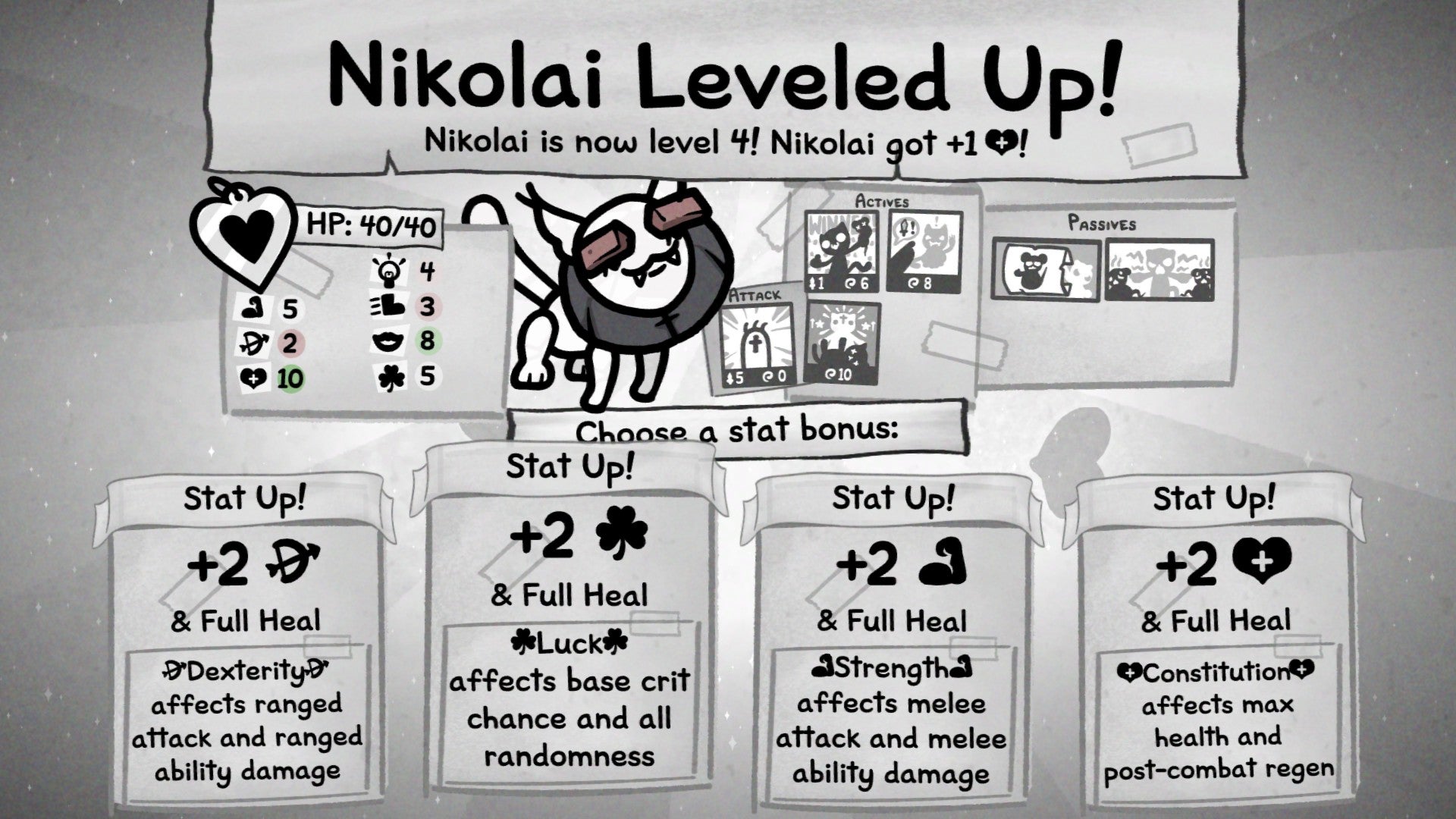

This is important, I can tell even now, because the turn-based stuff really isn’t screwing around. XCOM may be the closest touchstone but it isn’t a perfect match. Rather than Firaxis’ ingenious and much copied two-actions-per-turn design, Mewgenics opens things out a bit. You can move and you can attack each turn, but each cat also has a pool of mana that allows them to use various powers and abilities that they have been bequeathed, either by the random number game of birth genetics, or clever breeding, or the collar they’re given that denotes their class – healer, archer etc. etc. – or by levelling up and unlocking stuff on their run.

There are dozens and dozens of these abilities and they’re frequently brilliant. At the simple end you have something like a straightforward melee attack or a fur-ball ranged move, say, but very quickly you get interesting variants. One cat might have an attack that can also heal friendly units. Another might have a move that puts them in a certain position behind enemies: crucial for a game in which attacking from a certain angle gives you better results. Another might send a fly zipping across the screen or perform a dash attack. My favourite so far is a move that punches an enemy INTO SPACE for the rest of the turn before they land and do massive damage. (To themselves, happily.)

Caption

Attribution

Add on passives and you get really game-changing builds. On one run, for example, I was completely pummeled by an enemy that lobbed mines around the screen, mines that would slowly tick down and then explode inflicting harsh pain along rows and columns. Next time around I was dreading this guy, but I found out two of my cats on this run had passives that meant they did automatic spit attacks whenever anything moved within range, and so all this guy’s mines were automatically rendered useless. This is just one example. The passives in this game kind of rule.

Then there are things like the vermin and goop-heavy enemies – often disgusting, but always creatively designed and game-altering – and the environments you move through. Some will be littered with chunks of masonry you can use as cover. Others will have grass or patches of broken glass that alter your movement options. A lot of the attacks you’re given are elemental, so electrical attacks to an enemy standing in a pool of water will radiate outwards. Then you hit the sewer levels where pools of water shift around, moving units with them. Fire attacks are great until all that grass gamely catches light.

Caption

Attribution

Onwards the game unspools with new ideas, but the reason it remains rich rather than bewildering is that the ideas all make sense. You innately know what thorns are going to do to a unit. You know that taking your cat wearing paper armour into a lake is not going to be good for the paper armour. (Oh yes, there’s a rich item game in play, too. The things you can deck these cats out with.)

Mewgenics is the work of Edmund McMillen, as well as Tyler Glaiel, and there’s a lot of McMillen’s previous work in particular at play here. Games like The Binding of Isaac are a fascinating and distinctive blend of grot and high-powered thought, so it’s not rare to fight a bunch of feces monsters in the sewers in Mewgenics and then be frozen in place for a few seconds by the brilliant wording of a tooltip. The art is thick felt pen lines on the greys and blacks of wet newsprint. It’s instantly obvious who made this stuff.

If I have one point to leave you with – other than the fact that the soundtrack is rich with brilliant original songs – it’s this: the core of Mewgenics may be simple and familiar, but the game that unfolds across all these runs is huge, and obviously so, even from my position about nine or ten hours in. New classes, new abilities, new items, new environments, new ramifications to the cat breeding – not a sentence I type every day – make it clear even to a dimwit like me that twelve hours from now this is going to be a very different game to the one I think I’m playing at the moment. It’s cats, then, and they’re definitely all lunatics. But expect far more than three generations of them this time out.

One of the greatest things on earth is when you’re talking to someone you sort of know and they quietly switch from talking about human friends or family members to talking about their cats. It’s great because there’s often no meaningful alteration in tone to tell you something has changed. Cats are frequently introduced into conversation the same way a person might start talking about an intermittently beloved uncle who’s just out of prison. Cats are often delightful reprobates and oddballs. They’re needlessly, inventively cruel, or inhumanly calm and forbearing, or they’re ostentatiously silly. One will sit on the landing and swipe at everyone. Another will hide under a bath mat, certain that they have attained complete invisibility. They are known by their names but also by their behaviours.

The cats in Mewgenics are known by their behaviours.

Mewgenics – strange harmony here: Francis Galton, cousin of Darwin and originator of the racist pseudoscience of eugenics, also published a paper called Three Generations of Lunatic Cats – is all about cats and what they get up to. An easy way in might be to see it as a kind of XCOM for cats. You gather a gang of four cats and then take them out on a violent adventure, moving through different cat-adjacent spaces – caves, sewers – and engaging in turn-based battles with the various creeping horrors you find there.

In battles, the cats rove about a grid and use a variety of attacks or passive abilities to defeat everyone they’re up against before moving on. Each adventure is a kind of roguelite run, so alongside battles and bosses you’ll encounter little vignettes that could turn out to be good or bad – eat the mystery meat? – or treasure chests, or branching paths that allow you to take a different route depending on how good you’re feeling about your chances.

So why is it called Mewgenics and not, say, XCOM: Enemy’s Gone and Dumped on the Carpet? This is because after a run, you retire your cats and they go and live in a house together. Well, sometimes they do. Because where XCOM had a bit of base-building, Mewgenics has a whole machine that runs on cats. Strays come by and can be dropped into the house to then take out on new adventures. Retired cats can mate and create kittens that can grow up and – you’re with me – be taken out on new adventures with the former strays. Fine.

But then it gets weird. Because around your house is a whole town of people who will give you things in return for cats. This upgrade system is decidedly non-fun, and all the more brilliantly squeamish for it. Someone in town wants retired cats in return for adding a new room to your house. Someone wants kittens to teach you about cat ancestry. Someone wants dead cats. Of course they do. The machine that runs on cats chugs along and you exchange your cats judiciously to expand your house, to get a bigger stash, to learn more about the world of Mewgenics and cat breeding all that jazz.

Caption

Attribution

Oh yes, cat breeding. I’m still early on in this dazzlingly rich and complex game but I’m already understanding that success in the long term revolves around breeding cats and making sure you like the outcomes. Cats have traits and abilities that are useful in battle, but because you can only take a cat out for one roguelite run before it’s retired, you need to be careful about then breeding your retired cats to keep the traits and abilities you like in play. The right environment helps: certain rooms boost your chances of interesting mutations or of healing damage or of passing on better abilities. Further on in the breeding distance – this is a thing? – lies new class abilities, which opens the door to multiclassing. Hold me.

This is important, I can tell even now, because the turn-based stuff really isn’t screwing around. XCOM may be the closest touchstone but it isn’t a perfect match. Rather than Firaxis’ ingenious and much copied two-actions-per-turn design, Mewgenics opens things out a bit. You can move and you can attack each turn, but each cat also has a pool of mana that allows them to use various powers and abilities that they have been bequeathed, either by the random number game of birth genetics, or clever breeding, or the collar they’re given that denotes their class – healer, archer etc. etc. – or by levelling up and unlocking stuff on their run.

There are dozens and dozens of these abilities and they’re frequently brilliant. At the simple end you have something like a straightforward melee attack or a fur-ball ranged move, say, but very quickly you get interesting variants. One cat might have an attack that can also heal friendly units. Another might have a move that puts them in a certain position behind enemies: crucial for a game in which attacking from a certain angle gives you better results. Another might send a fly zipping across the screen or perform a dash attack. My favourite so far is a move that punches an enemy INTO SPACE for the rest of the turn before they land and do massive damage. (To themselves, happily.)

Caption

Attribution

Add on passives and you get really game-changing builds. On one run, for example, I was completely pummeled by an enemy that lobbed mines around the screen, mines that would slowly tick down and then explode inflicting harsh pain along rows and columns. Next time around I was dreading this guy, but I found out two of my cats on this run had passives that meant they did automatic spit attacks whenever anything moved within range, and so all this guy’s mines were automatically rendered useless. This is just one example. The passives in this game kind of rule.

Then there are things like the vermin and goop-heavy enemies – often disgusting, but always creatively designed and game-altering – and the environments you move through. Some will be littered with chunks of masonry you can use as cover. Others will have grass or patches of broken glass that alter your movement options. A lot of the attacks you’re given are elemental, so electrical attacks to an enemy standing in a pool of water will radiate outwards. Then you hit the sewer levels where pools of water shift around, moving units with them. Fire attacks are great until all that grass gamely catches light.

Caption

Attribution

Onwards the game unspools with new ideas, but the reason it remains rich rather than bewildering is that the ideas all make sense. You innately know what thorns are going to do to a unit. You know that taking your cat wearing paper armour into a lake is not going to be good for the paper armour. (Oh yes, there’s a rich item game in play, too. The things you can deck these cats out with.)

Mewgenics is the work of Edmund McMillen, as well as Tyler Glaiel, and there’s a lot of McMillen’s previous work in particular at play here. Games like The Binding of Isaac are a fascinating and distinctive blend of grot and high-powered thought, so it’s not rare to fight a bunch of feces monsters in the sewers in Mewgenics and then be frozen in place for a few seconds by the brilliant wording of a tooltip. The art is thick felt pen lines on the greys and blacks of wet newsprint. It’s instantly obvious who made this stuff.

If I have one point to leave you with – other than the fact that the soundtrack is rich with brilliant original songs – it’s this: the core of Mewgenics may be simple and familiar, but the game that unfolds across all these runs is huge, and obviously so, even from my position about nine or ten hours in. New classes, new abilities, new items, new environments, new ramifications to the cat breeding – not a sentence I type every day – make it clear even to a dimwit like me that twelve hours from now this is going to be a very different game to the one I think I’m playing at the moment. It’s cats, then, and they’re definitely all lunatics. But expect far more than three generations of them this time out.

6 comments