Pat Oleszko has been making a fool of herself full time for 60 years. Known for her satirical wit, surreal costumes, and performances in and around immense inflatables, the artist defies easy categorization. Using her body as the armature for a unique sort of walking, talking “pedestrian art,” Oleszko has inhabited incendiary and far-flung guises including a rapacious Coat of Arms(1972), a robed and miter-clad Nincompope (1999), and, in recent years, a caricature of Dumpty Trumpty (2018). For Oleszko, the performance never stops and the costume’s never off, whether on the street or onstage, nude or covered from head to toe.

The upstart Midwesterner spent her formative years in the 1960s at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, then a crucible of experimental time-based art. In that milieu, she brushed shoulders with Andy Warhol, listened to lectures by visitors from Claes Oldenburg to the Velvet Underground, and went to performances collectively staged by the ONCE Group, Robert Rauschenberg, John Cage, and Judson Dance Theater. Realizing that she could express her ideas in the way she presented herself in the everyday, her wardrobe exploded to fit all occasions, and she began making appearances at ONCE Group events and the Ann Arbor Film Festival.

When Oleszko moved to New York in 1970, an art world gripped by Minimalism and Conceptual art didn’t quite know what to make of her subversive humor and ostentatious getups. She created her own opportunities to perform, walking city streets in absurd attire and infiltrating Thanksgiving and Easter Day parades. Before long, she got invitations to exhibit and perform at the Museum of Modern Art, the Kitchen, P.S. 122, and the Whitney Museum.

Now, at the age of 78, Oleszko is being recognized by two New York bastions of contemporary art: the Whitney Biennial and SculptureCenter, the latter of which is presenting (through April 27) the artist’s first institutional solo exhibition in the city in more than 35 years. A.i.A. spoke with Oleszko about her multidisciplinary trajectory and flirtations with the absurd.

Your practice originated in over-the-top costumes. How has it shifted scope and format over the years?

In the beginning, the costumes were a kind of octopussian exploration of anything that I found attractive, challenging, or comment-worthy. I was always wearing the inside of my head on the outside of my body. There was no name for performance art when I started working. There were artists doing events that responded to “happenings.” But I needed to discover what I was doing, using my body as the platform for experimentation. I did everything with my costumed personas. The world is my stage. The world is my stooge.

I street-walked, joined protests and parades, attended parties. I did time-based events. I made performances on film. I entered a striptease contest and beauty contests like Miss Subways and Miss Polish America. I waitressed at Max’s Kansas City and the St. Adrian Company, and every night I costumed so that people would come in just to see who I was that evening. I also did burlesque, which was another means of discovering what to do with wearable sculptures—to take things off, put things on, become a character. At some point, I started using my works as illustrations, calling them “visual editorials.” Those have been in Artforum, Esquire, Ms., Oui, Penthouse, Playboy, and even Sesame Street Magazine and National Geographic.

Is there a medium you’ve come to identify with most strongly?

They’re meshed together in the great Osterizer in the sky. But I’m a sculptor, essentially, who makes work that lives, breathes, walks, farts, and fucks. My body is the expression of the initial idea. The work’s never separated from myself. I’m its vehicle. It was a big deal when I could finally let other people wear my costumes, which were so much a part of my journey of finding out who I was.

How did your disparate activities begin to cohere into longer performances?

In 1976, I had the opportunity to do an evening-length piece at the Museum of Modern Art. I had no idea how to do that at first, but I started stringing things together. The performances weren’t necessarily propelled by a storyline, but they focused on ideas that I’d hit at in lots of different ways. Once I could perform on a stage, I started to do shows at the Kitchen, P.S. 122, and places across Europe.

What did you learn from your time working in burlesque?

I did that off and on, so to speak, for a couple of years in college as “Pat, the Hippie Strippy.” It was an enormously informative and inspiring subculture that was on its way out—the last vestiges of vaudeville. They had comedians at the theater where I worked who would do acts with the girls, making all these double and triple entendres that I, of course, loved.

Did that impact your pacing and sense of narrative? The multiact structure of your performances parallels that of vaudeville or variety shows.

In the variety show, there’s a new act every five minutes. I adopted that and manipulated it into my own thing. As the only person onstage, I’d multiply myself and turn different parts of my body—fingers, knees, butt, breasts, and pussy—into smaller characters.

Listening to an artist talk you gave in the ’80s, I was struck that it had the cadence of standup comedy. How did you arrive upon humor as a strategy?

As an artist, you’re compelled to work in ways both instinctive and intellectual. I have a definite theatrical bent, ranging from comedy to tragedy. My muse is a-muse. And I’m constantly amused by what the human animal does in pursuit of acceptance. The people I admire—Buster Keaton, Lewis Carroll, Jacques Tati—were brilliant at pointing out the foibles of society, the wonder of man as a barely thinking animal. That’s what propels me. I see inadequacies that I want to point out or correct. I do so through absurdity, which mostly happens to be funny, though sometimes it’s not. It’s a double whammy. You can laugh at something and then think, “Oh, jeez, what was I laughing at? She was talking about the end of the world.”

You’re like a court jester, given license to say bad things.

You get credibility if you’re a fool. You can say things, do things, manipulate things. I’m often making statements about topics that I want people to pay closer attention to—climate change, women’s rights, politics, and inequity and absurdity wherever I see it.

You’ve described your work as a kind of sociological experiment. You enter environments as a catalyzing event. How do people react?

It depends on the situation, the costume, and what level I’m operating on. Is it a critique or not? Sally Sex-retary (1971) can have 500 men following her down Wall Street in an absurd costume—you know, all tits and ass. Or I can walk out onto the street in my neighborhood and not get any response. There are some outfits that you can’t not look at. Every pair of eyeballs sees me, follows me from the minute I leave the house to the minute I escape. It’s very demanding to be the center of attention, with no place to hide. As the fool, I’ve taken it on as my burden. I’m not going out unless I’m ready to be a peacock, to complement the situation, to disturb things.

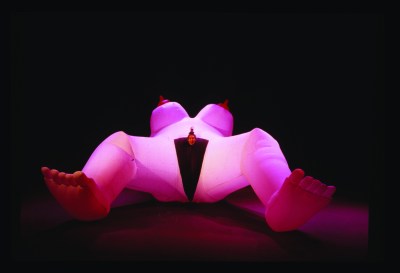

Many of your installations and performances incorporate inflatables that you design and construct yourself—a Grecian temple, an astronaut, the legs and feet of the Wicked Witch of the West. What first gave you the idea to work with inflatables?

I saw something that could blow up in a coffee shop and said, “Oh, I can make inflatable things, only I’ll make them a little larger than that.” It became a way for me to make big sculptures, which was one of the problems that I had been trying to solve by using my body as an armature. It took me a little while to figure out the air, the right fabric, and how I could actually use them in a performance. I began to inhabit them, using their interior and exterior spaces. They were great onstage. You could inflate one in a minute. It was this kind of surprise, or organic magic. Then you unzip it and boom, it’s gone. That’s one of the beauties of the inflatables—there’s no there there.

How does it feel to have both a solo exhibition up at SculptureCenter and work in the Whitney Biennial?

In the Whitney Biennial, I’m showing a giant inflatable. I’m usually a pedestrian-size sculpture, but I just might have the tallest and smallest pieces in the show! The exhibition at SculptureCenter—“Fool Disclosure”—is a survey concentrating on the sculptural works. When they asked, I said, “I’m going to jam as many inflatables in as I can.” It expanded to include films, hats, and some of my really early works. There’s also a catalog, which includes more than 100 names that I came up with for the exhibition. My partner suggested “Pat Oleszko: Nice Hair.” I’ve been telling everybody—everybody!—that I’m going to be in two institutions at the same time. Someone worried, “She’s institutionalized in two places?!”

That’s also a good title. “Pat Oleszko: Institutionalized.”

I’ll add it to the list.

Source URL: https://www.artnews.com/art-in-america/interviews/pat-oleszko-fool-sculpture-center-performance-whitney-biennial-1234771648/